“Saving=Investment” is axiomatic in macroeconomics as it is taught in basic textbooks, found in advanced research and assumed in national statistics. Yet it is a fallacy which can be traced to Keynes (1936, p.63) where he defined saving as “the excess of income over consumption” in a framework of equilibrium circular flow of national income.

This is a fallacy because the economy is generally not in equilibrium in each period (i.e. income is not equal to expenditure). The excess of income over expenditure is adjusted in the national accounts by introducing a term called “statistical discrepancy” or “net borrowing or lending” (in the US) in order to force equality in the statistics. It is this important discrepancy which is actually the aggregate saving rate because it is defined by income minus expenditure for each period.

The “excess of income over consumption” is literally the rate of unconsumed surplus which could be invested or saved in each period. Hence, in each period the rate of investment and the rate of saving are distinct and mathematically unrelated quantities. It makes no sense to assert “saving=investment”. The correct accounting equation for the disequilibrium flow of national income is

Surplus = Saving + Investment,

where “Saving” or the rate of saving is linked to the national balance sheet which accounts for national assets and liabilities. Saving is a withdrawal from income flow and accumulates as the stock of national saving for future expenditure. Without this new interpretation of income flow, there can be no stock of national saving since, if “income=expenditure” in each period, then “surplus=investment” and all unconsumed surplus is invested back into the equilibrium income flow – there can be no saving accumulation outside the flow.

The equilibrium framework cannot properly describe the disequilibrium processes of our world. For example, equilibrium theory cannot be used to describe secular trends, such as the “secular stagnation” notion of Hansen (1939) recently resuscitated by Summers (2013).

Secular trends are naturally observed with a disequilibrium interpretation of US national income data supplied by BEA (2014). The US national saving rate is not just low, as commonly believed, but has been substantially negative (up to nearly 6 per cent of GDP) for the past few decades. Recently, Greenspan (2014) has observed accurately, “we are eating our seed corn”, as over the decades, past and future US savings have been consumed.

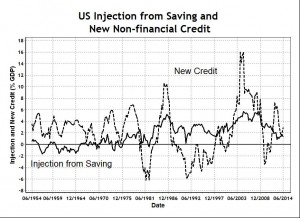

In a previous post, it was shown that continual Keynesian economic stimulus had led to US over-consumption (high propensity to consume) which is arithmetically equivalent to under-investment (low propensity to invest). Keynesian economic collapse would have occurred during the global financial crisis, had it not been for more saving and new credit injection into US economic flow to augment national income.

A significant part of measured economic growth since 1980 has come from the injection of past and future saving and new credit into the national income flow.

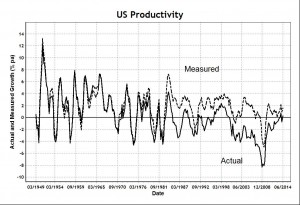

The cumulative saving injection into the economy leads to running down the national stock of saving by over ten trillion dollars. If the measured economic growth is adjusted for the fact that a significant part of it was not related to economic production, then the actual economic growth appropriate for calculating productivity shows that the productivity growth rate is not just low or falling, as commonly believed, but has been substantially negative since 2000.

The secular stagnation (or more accurately, the secular decline) of the US economy may be attributed to the secular decline in production, and therefore productivity, which may also explain the relative decline of wages and salaries and the rise of income inequality. Increasing share of disposable income has come, not from production, where workers are required, but from government transfer payments and from dividends and capital gains of asset markets.

Based on equilibrium theory, Summers (2013) proposed that the solution to secular stagnation was more of the same - lower or negative real interest rates - whereas Hansen (1939) had already cast doubt on such an idea:

Yet few there are who believe that in a period of investment stagnation an abundance of loanable funds at low rates of interest is alone adequate to produce a vigorous flow of real investment.

Indeed, real investment drives economic growth through production (Sy, 2014). Financial investment has no direct impact on economic production. Low interest rates, which inflate asset bubbles, make financial investments relatively more attractive than real investment. Big banks prefer the liquidity of financial markets and find financial speculation far more profitable than the relatively illiquid and risky business of traditional lending to enterprises, particularly to small business. Financial markets, where saving and investment are mostly directed by policy, may have little impact or even detrimental impact on the real economy.

A full version of this paper was submitted to Norbert Haering of the World Economics Association (WEA) for its forum for open peer discussion. The paper was rejected out of hand because I was “inventing the wheel without paying significant attention to related literature, like the one on stock-flow-consistent models. This is the most important point.” How this criticism can be relevant is a mystery, because the paper treats a single sector (the nation) and is therefore trivially stock-flow-consistent, since there is no need to keep track of inter-sectoral flows.

The economic establishment, including academics, governments, central banks, mainstream media and big businesses, uses its power to manipulate data, information, opinion, markets, laws and behaviour to drive the global economy to endogenous crisis (Sy, 2012). Its power to ignore facts and contrary evidence to preserve the unscientific economic paradigm makes it very likely that the current policy trajectory will continue until economic collapse.

Keynes had been criticized before for trying to shoehorn dynamic elements into the static general equilibrium model.

I do not recall that this is how Keynes explicit defined savings in this framework, but I am going to take this at face value until my replacement copy of "The General Theory" arrives. I would ask whether the ex-post / ex-ante distinction comes into play here. Again, I seem to recall that ex-post, Savings = Investment by definition, but this may not even be right in in economy so thoroughly dependent on credit as models capitalist economies are. Your Surplus = Savings + Investment may be a better place to start.

From a person that has been trained in economics, but who has also read fairly widely in philosophy and history, I have never really bough into the idea that savings = investment in some automatic infallible way. Since market economies have shown fluctuations and instability throughout their history, it has always struck me as bizarre that these could be 'explained' or modeled by a system that exhibits stability, and which is only disturbed by random shocks. In one of life's little ironies, business cycles were one phenomena observed by economists and economic thinkers in the 1800s, and attempts to correlate business cycles with other phenomena gave birth over time to econometrics. Jevons' Sunspot theory fits into this category. Even if false, it was an attempt to connect an observed series of facts or data with a suspected cause. (See Morgan, Mary S. The history of econometric ideas. New York: Cambridge University Press)

Keen's "Debunking Economics" and Robert Guttmann's "How Credit Money Shapes the Economy." also highlight the role of money and credit. So some idea about what money is, what credit and debt are, is key. Once we have this, endogenous cycles seem to follow quite easily.

One last idea - investment in new products and production processes generates new technology from within the system. Businesses seek competitive advantage over their rivals, and they require money and credit to do so and measure the results. So here we have the intersection of the definition of money and the purpose of investment in the real physical side of the economy as a source of problems, which is only made worse by increasing importance/dominance of finance.

Jeff, Thank you for your comments. I want to emphasize that I have merely established some facts from the data. The assumption "saving=investment" requires equilibrium, if not at every instant in time, at least on average over a measurement period. The US data show income less than expenditure consistently over years and decades - which is incompatible with equilibrium.

Many have questioned the equilibrium assumption, including Joan Robinson, a Cambridge colleague and disciple of Keynes. Towards the end of her life, Robinson (1985) wrote in her 1980 "spring cleaning" paper:

I have shown that the data make a lot more sense without the equilibrium assumption. So why make the assumption? "I have no need of that hypothesis" said Laplace to Napoleon, when asked about God in his theory of the planets. The God of equilibrium still rules economics.

There are too many theories in economics and not enough agreement on the facts. It is impossible to have science without generally agreed facts.

Confused confusers. Comment on 'Saving=Investment Fallacy'.

You write: “Saving=Investment” is axiomatic in macroeconomics as it is taught in basic textbooks, found in advanced research and assumed in national statistics. Yet it is a fallacy which can be traced to Keynes (1936, p.63) where he defined saving as “the excess of income over consumption” in a framework of equilibrium circular flow of national income.”

You put the finger exactly on the critical error/mistake. To see this clearly, however, one has to take the decisive analytical step. Keynes's problem started with profit.

“His Collected Writings show that he wrestled to solve the Profit Puzzle up till the semi-final versions of his GT but in the end he gave up and discarded the draft chapter dealing with it.” (Tómasson und Bezemer, 2010, pp. 12-13, 16)

Now comes the chain reaction of errors/mistakes: When profit is not correctly defined, income is not correctly defined, and then saving is not correctly defined. It is with profit where the confusion about saving “equals” investment starts. The conceptual mess has been verbally papered over with ex ante/ex post and the representative economist has swallowed all this hook, line and sinker.

For the formally correct solution see my recent paper (2014). It should be mentioned that there is monetary and nonmonetary profit and correspondingly monetary and nonmonetary saving. Here we deal exclusively with monetary profit and saving.

Because neither Keynes nor the Post-Neo-New Keynesians have solved the profit puzzle and with it the saving-investment puzzle, they are out of science (2013).

The profit theory of Keynes, Kalecki, or Keen, for example, is as far away from reality as any mainstream profit theory, surely therefore, both Heterodoxy and Orthodoxy “fail to capture the essence of a capitalist market economy.” (Obrinsky, 1981, p. 495)

Economists owe the world the true economic theory, that is, a theory that satisfies the scientific standards of material and formal consistency and that explains how the economy works.

Formal consistency requires to start with an objective set of axioms and then to proceed in the logically correct way. I=S is the widely visible monument of confused thinking and lack of genuine scientific instinct of both Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2013). Why Post Keynesianism is Not Yet a Science. Economic

Analysis and Policy, 43(1): 97–106. URL http://www.eap-journal.com/

archive/v43_i1_06-Kakarot-Handtke.pdf.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). The Three Fatal Mistakes of Yesterday Economics:

Profit, I=S, Employment. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2489792: 1–13. URL

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2489792.

Obrinsky, M. (1981). The Profit Prophets. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics,

3(4): 491–502. URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/4537615.

Tómasson, G., and Bezemer, D. J. (2010). What is the Source of Profit and

Interest? A Classical Conundrum Reconsidered. MPRA Paper, 20557: 1–34.

URL http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/20557/.

***

Here is the correct equation that relates profit Q, distributed profit YD, investment

expenditure I, and household sector saving S:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AXEC09.png

***

For equilibrium as a nonentity see:

http://rwer.wordpress.com/2014/11/06/still-dead-after-all-these-years-general-equilibrium-theory/#comment-82985

***

This comment has been composed with copy/paste-text from LYX and copy/paste-references from the PDF. The resulting formatting above may therefore be not as perfect as it should.

Egmont, I agree with you (on your blog) that axioms are important in formal theory. Mostly, economists only philosophize about economics. They generally do not theorize about economics by setting out their assumptions clearly and explicitly, as required by science. Hence, facts, assumptions, conjectures and hypotheses are often completely confused.

Economics research papers are generally badly written, because they pretend economics is a science and inappropriately imitate how physicists write their research papers. A physicist can motivate the reporting of new research by citing past research papers on the same topic. This mode of presentation is appropriate because physics has already reached a solid body of consensual knowledge and new research is usually just building on existing research.

In most physics research, there is no need to define or discuss basic concepts such as mass or energy or laws of conservation of energy, the constancy of the speed of light, etc, because they are consensual knowledge already embedded in most research publication. Economics is at nothing like this stage of epistemological development.

Basic axioms such as "saving=investment" has never been checked against empirical evidence. Yet that axiom is the foundation of Kalecki's theory of profits (1942), which you should have, but had not, mentioned in your "Three Fatal Mistakes" paper. Kalecki's paper contains mostly unnecessary mathematics based on false assumptions such as "saving=investment" and the assumption that workers don't save, which is contradicted today by workers' huge pension funds all around the world. In Australia, total workers' saving handily exceeds the country's GDP.

You may agree that 99 percent of economics research papers should never have been published, because they are either building fallacies on fallacies, only with more and more ugly and incompetent mathematics over time, or, just arguing against other rhetorical arguments, without any advance on economic truths. Much of the rubbish is due to "publish or perish" syndrome of flawed academic management.

For example, take Weintraub's paper (in your list of references) on "Joan Robinson's critique of equilibrium: an appraisal", published in the very top ranking journal: The American Economic Review. He attacked Robinson on her critique of neo-Walrasian program, simply because it is a program, saying "...all the theories are based on a certain set of presuppositions shared by all who work in the program. The organizing center of the program is called the hard-core, which contains propositions taken as given by adherents to the program." and "Assailing the logic of hard-core propositions, as she did, is an exercise based on misunderstanding."

Research programs cannot be criticized! Not for one moment did Weintraub addressed whether the "role of equilibrium in the neo-Walrasian program" is justified or not based on any objective criteria - essentially equilibrium is a hard-core assumption in a program and therefore Robinson cannot criticize it! Weintraub was adding noise to the literature, like most economists.

The equilibrium axiom in much of economics is false, not supported by empirical evidence. Whenever the equilibrium assumption is used in economics research, it should be justified, rather than accepted as true or obvious. In any scientific theory, an axiom may be unrealistic, but it cannot be false, as you may agree - an axiom needs to be checked that it is not be obviously falsified by factual evidence.

No more critique of economics, please!

Comment on admin

In its present state, economics is unsatisfactory. Most economists can agree with this. It is not surprising then that complaining and debunking has almost become a sub-discipline of economics. Not much can be said against this, except that it is a detour. As Schumpeter already noted:

“If we feel misgivings nevertheless, all we have to do is to start appropriate research. Anything else is pure filibustering.” (1994, p. 577)

Or, Blaug, in even stronger words:

“The moral of the story is simply this: it takes a new theory, and not just the destructive exposure of assumptions or the collection of new facts, to beat an old theory.” (1998, p. 703)

The problem is that conventional economics has so many obvious defects that it is not at all clear where to start. Here, Keynes pointed the way:

“For if orthodox economics is at fault, the error is to be found not in the superstructure, which has been erected with great care for logical consistency, but in a lack of clearness and of generality in the premises.” (1973, p. xxi)

And this leads back to the question that J. S. Mill posed at the very beginning of theoretical economics:

“What are the propositions which may reasonably be received without proof? That there must be some such propositions all are agreed, since there cannot be an infinite series of proof, a chain suspended from nothing. But to determine what these propositions are, is the opus magnum of the more recondite mental philosophy.” (2006, p. 746)

And this leads even further back to the beginning of science:

“When the premises are certain, true, and primary, and the conclusion formally follows from them, this is demonstration, and produces scientific knowledge of a thing.” (Aristotle, Analytica, URL https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Posterior_Analytics)

The premises of Orthodoxy are uncertain and false and this fully explains its failure. What exactly are the premises?

“As with any Lakatosian research program, the neo-Walrasian program is characterized by its hard core, heuristics, and protective belts. Without asserting that the following characterization is definitive, I have argued that the program is organized around the following propositions: HC1 economic agents have preferences over outcomes; HC2 agents individually optimize subject to constraints; HC3 agent choice is manifest in interrelated markets; HC4 agents have full relevant knowledge; HC5 observable outcomes are coordinated, and must be discussed with reference to equilibrium states. By definition, the hard-core propositions are taken to be true and irrefutable by those who adhere to the program. ‘Taken to be true’ means that the hard-core functions like axioms for a geometry, maintained for the duration of study of that geometry.” (Weintraub, 1985, p. 147)

Note well that these axioms have only taken to be true and irrefutable by the adherents of Orthodoxy. They are by no means irrefutable for anybody else.

“If a professional group regards itself a having a message to deliver to others than its own members and makes any public claims in that respect, it thereby gives others the right to scrutinize the methods whereby that message was discovered, including the principles, or possibly prejudices, followed in choosing premises. They continue to do so. Cunningham in 1891 remarked that in the choice of premises ‘it is not always easy to tell when a professor of the dismal science is making a joke’ and I suspect that Cunningham meant that if the professor was not joking, then he was making a fool of himself.” (Viner, 1963, p. 12)

So, everyone who does not want to make a fool of himself has no choice but to come up with a new set of axioms (see 2014).

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Blaug, M. (1998). Economic Theory in Retrospect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 5th edition.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). Objective Principles of Economics. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2418851: 1–19. URL http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2418851.

Keynes, J. M. (1973). The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes Vol. VII. London, Basingstoke: Macmillan. (1936).

Mill, J. S. (2006). Principles of Political Economy With Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy, volume 3, Books III-V of Collected Works of John Stuart Mill. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund. URL http://www.econlib.org/library/Mill/

mlP.html. (1866).

Schumpeter, J. A. (1994). History of Economic Analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Viner, J. (1963). The Economist in History. American Economic Review, 53(2): pp. 1–22. URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/1823845.

Weintraub, E. R. (1985). Joan Robinson’s Critique of Equilibrium: An Appraisal. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 75(2): 146–149. URL

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1805586.

Egmont, I disagree with you (and Blaug) for the following reasons.

Firstly, past critiques of economics have had little impact precisely because they are merely different "new" opinions or theories attempting to replace the prevailing theory. How do you know (or prove) that your new set of axioms is better than the old set? If it is only a new idea, without experience, against an old idea with centuries of experience, then it has always been to stick with the devil you know. Failure of past critiques does not imply critiques should stop, but rather new types of critique are required.

Secondly, it is not even clear in a formal sense what are the axioms of the existing economic paradigm - economics has not been developed in a scientific way (with clear axioms). Most economists do not even recognize what assumptions they are making or what economic theories are currently driving government policies and affecting the world. For example, the heterodox Keynesians (e.g. RWER) are blaming neoclassical economics for the ills of the world, whereas I have shown from data that governments have been pursuing Keynesian macroeconomic management for decades.

Thirdly, we don't have the luxury of waiting years or decades for a new theory to replace the old. You said, "In its present state, economics is unsatisfactory. Most economists can agree with this". But do they know exactly what is unsatisfactory? For example, if they knew that increasing the Keynesian multiplier has the opposite effect to what they are intending (to increase economic growth), then wouldn't stop doing what they have been doing be beneficial to the economy? We don't need a new theory to improve the world - just stop doing stupid things will do. A theory that does harm is worse than no theory at all.

Fourthly, a new set of axioms is not the beginning of a new theory for scientific investigations, rather it is at the end of years of facts gathering, analysis, modelling, hypotheses testing etc. For example, the axiom that the speed of light is constant is a fundamental assumption of the theory of relativity - it took Michelson, Morley and others 50 years of checking to verify it. Most recent test in 2009, put the accuracy of the constant to 17 decimals.

Fifthly, economists do not recognize facts, because they are used to "observation-less theorizing". They do not even recognize when the facts of observation contradict their theories. Or if they do recognize, they choose to ignore it. Under such situations, what is the use of a new theory? Without some objective criteria to decide on the relative merits of theories, one theory is as good as another, just like one religion is as good as another.

Finally, you have to decide what your new set of axioms or theory is intending to achieve. Is it just a new mousetrap to replace the old one? Is it a mouse you want to trap? That is, do you want your new set of axioms or a new theory to allow you to predict and control the economy? It may not be that mouse you want to trap, because prediction may not be possible. You are making a meta-assumption: economic theory can have the same predictability as physics theories.

You ought to let me investigate the facts and test them against existing theories, without complaining that I'm making another (useless) critique of economics, as you assert that everyone is already well aware. Revealing new facts of observation is not useless and it only happens to be a critique simply because the facts are inconsistent with theory. I'm doing real scientific work here, where patience is needed for making real progress. I won't complain about your axioms.

Testing is better than critique. Comment on admin.

I certainly do not want to stop you from testing existing theories. Just the contrary, I explicitly encourage testing of the structural axiom set and its logical implications in my mission statement http://www.axec.org/#!identity/c1i98

and elsewhere in my papers.

This brings me right back to our starting point. So, let us put methodological questions for a moment aside. You said that I=S is a fallacy. I agree. Not only this, I present the correct relation. It is this one:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AXEC09.png

This is the relation for the investment economy. It gets a bit more complex if foreign trade and government is included. But that is not the point at issue at the moment. The equation says that household sector saving and business sector investment are never equal. And this is sufficient in the first round to empirically refute the standard approach.

Now the rest is quite simple. You have the data. A cursory comparison of the data with the formula above will convince you that the formula is essentially correct. Then the crucial test has to be designed.

What will the outcome of this test be? The structural axiom set will be corroborated with an accuracy of two decimal places. This is how science works:

“Whether an axiom is or is not valid can be ascertained either through direct experimentation or by verification through the result of observations, or, if such a thing is impossible, the correctness of the axiom can be judged through the indirect method of verifying the laws which proceed from the axiom by observation or experimentation. (If the axiom is deemed to be incorrect it must be modified or instead a correct axiom must be found.)” (Morishima, 1984, p. 53)

This answers the first question of your comment: “How do you know (or prove) that your new set of axioms is better than the old set?” Then, obviously, there is no urgent need to discuss the rest.

In light of your comment, a better title of my previous contribution would have been: No more filibuster about economics, test the axioms!

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Morishima, M. (1984). The Good and Bad Use of Mathematics. In P. Wiles, and G. Routh (Eds.), Economics in Disarry, pages 51–73. Oxford: Blackwell.

Egmont, I repeat: "I won't complain about your axioms".

It is not a matter of complaint, or taste, or feeling, it is a matter of method, which implies testing:

“Reason gives the structure to the system; the data of experience and their mutual relations are to correspond exactly to consequences in the theory. On the possibility alone of such a correspondence rests the value and the justification of the whole system, and especially of its fundamental concepts and basic laws. But for this, these latter would simply be free inventions of the human mind which admit of no a priori justification either through the nature of the human mind or in any other way at all.” (Einstein, 1934, p. 165)

References

Einstein, A. (1934). On the Method of Theoretical Physics. Philosophy of Science,

1(2): 163–169. URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/184387.

Egmont, I have already cited a very clear statement from Einstein in What is Science?:

Axioms (as well as testing) have to be based on experience (i.e. facts of observation). A scientist would only consider axioms which are supported by empirical evidence. That is, "pure logical thinking" alone cannot create scientific axioms. So at this stage, there appears to be no scientific theory of economics. The purpose of this blog is to develop a science of economics.

All problems settled -- free way ahead. Comment on admin.

It is gratuitous to play ping-pong with Einstein quotes and to cook up the induction-deduction discussion once more. Schumpeter has already settled the matter.

“... there is not and cannot be any fundamental opposition between ‘theory’ and ‘fact finding,’ let alone between deduction and induction.” (1994, p. 45)

Science is about two, repeat two, consistencies: “Research is in fact a continuous discussion of the consistency of theories: formal consistency insofar as the discussion relates to the logical cohesion of what is asserted in joint theories; material consistency insofar as the agreement of observations with theories is concerned.” (Klant, 1994, p. 31)

However, as a practical matter, theory comes first: “Indeed, there is no such thing as an uninterpreted observation, an observation which is not theory-impregnated.” (Popper, 1994, p. 58)

Those common sense people who are stating the seemingly plain fact that 'the sun goes up' do simply not realize that they are stating a hypothesis.

Theory in the proper sense is a free invention, the product of pure thought, and, lo and behold, this is exactly what Einstein said (note that he never observed a relativistic effect that kicked off his thinking):

The same holds, of course, in theoretical economics. Political economists, though, are too much occupied with pushing their agendas. Thus, they have neither time nor brainspace left over for thinking.

So there is absolutely no problem here. Take the structural axiom set or one of its logical implications and test them. Thus, you and I together are doing really good science.

To recall, those who have filibustered about induction-deduction have achieved nothing of scientific value until this sunny morning and will not in the foreseeable future.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Einstein, A. (1934). On the Method of Theoretical Physics. Philosophy of Science, 1(2): 163–169. URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/184387.

Klant, J. J. (1994). The Nature of Economic Thought. Aldershot, Brookfield, VT: Edward Elgar.

Popper, K. R. (1994). The Myth of the Framework. In Defence of Science and Rationality., chapter Science: Problems, Aims, Responsibilities, pages 82–111. London, New York, NY: Routledge.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1994). History of Economic Analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Egmont, The idea that theory is "free invention" or "pure thought" is grossly exaggerated. Of course you can invent any elaborate theory you like from pure thought (like most of economics), but it would not be a scientific theory and usually has little relation to reality.

The idea that theory precedes empirics is also grossly exaggerated. It is true that some theoretical concepts are pure thought and they necessarily precede empirics. For example, you cannot use or test a conceptual idea until you have theoretically conceived it. The concept of energy precedes the discovery of the law of conservation of energy.

But "theory precedes empirics" does not mean economic theory is more important than economic facts or reality. This is an economic epistemological fallacy. Most economic theorists waste their time building more and more sophisticated mathematical models which are based on false or unverified assumptions. The theories don't work (however elaborate) because they have false foundations divorced from reality.

In my opinion, any theory with more than one unverified assumption is likely to be scientifically useless, because a failed test (usually the case) tells you nothing about what to do with your theory next: how to modify it to match reality. For example, the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) has never been scientifically tested, because all empirical tests have been joint tests of EMH and the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), which is an equilibrium model. Failed empirical tests tell us objectively nothing about EMH or CAPM, as one, the other, both or neither may have failed.

Science is a patient step-by-step process, testing one axiom at a time. It is not useful to test "one logical implication" of a set of unverified axioms, because a successful result could be a fluke and a failed result tells us nothing about any possible offending axioms.

The relationships between theory and empirics, induction and deduction have been discussed in What is Science?. Most people who talk about science (e.g. Popper, Hayek), have never done any science, let alone created a scientific theory. With this comment, I will terminate our discussion and will concentrate my efforts on developing a science of economics.

Thank you very much for your contribution to this post. It has been stimulating.