Before the latter parts of the nineteenth century, no one understood the origins and causes of diseases, because the ideas of germs and bacteria were not fully conceived. Medicine was not science. There was no systematic account of diseases or records of their failed remedies from the use of all sorts of potions, snake oils and therapies. Without an empirical foundation and pathology, doctors were quacks and charlatans who recycled the same snake oils for curing illnesses.

Economics is not science. The current stage of development is equivalent to pre-nineteenth century medicine. Current knowledge is insufficient to understand or solve many economic problems – its claims otherwise are quackery. Just like in medicine, the quackery continues since no one has discovered and proved the right answers to gain widespread acceptance. The economic profession is a disgrace because it prevents economics from being a science by protecting a system of “closed shops.” Economic education is a lobotomy performed at different universities by different economic schools.

The charlatans have not understood or have refused to accept that their own ideas have caused endogenously the global financial crisis (GFC), which was why they did not see it coming. Without acknowledging this, nothing much has changed. Academics are still just telling stories and mistaking them for theories (Lucas, 2011). The same failed theories and remedies are being dressed up as new ideas to fix the ills of our economy. They are too blind to facts and too ignorant of economic history to know that most their policy ideas have already been tried with mixed results at best and outright disasters at worst.

Secular stagnation of the US economy (Summers, 2015) and wealth inequality (Piketty, 2014) have brought out charlatans with their snake oil cures. Their solution is the old chestnut of socialism, where full employment and wealth equality are guaranteed for all. Socialism is now openly “revived” in the US, where most do not recognize that already there have been decades of creeping socialism which most people have mistaken for capitalism.

The “new” socialism through Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a form of monetary socialism which is defined below. Essentially, the “insight” of MMT is that a sovereign nation has total control of its finances through its ability to create fiat currency “out of thin air”. This is the MMT key to implementing socialism where government budget deficits do not matter and full employment can be guaranteed. However, the proposed nirvana has already been achieved historically under communism in some countries where neither government deficit nor unemployment existed, and there was no inflation and no need for money.

In the current fiat currency system, MMT rightly dismisses (Mosler, 2010) many inaccurate statements on economic policy constraints based on government finances. However, MMT is mesmerized by the mechanics of currency, without paying adequate attention to real economics. The MMT snake oil for the economy suffers from many economic fallacies; three of the most important ones relating to the “money illusion” are discussed here.

Money Fallacies

MMT has its roots in chartalism (Knapp, 1924) which assumes erroneously that the state has complete control of money because it can enforce its fiat currency as legal tender and can adjust the quantity of money through issuance and taxation. Chartalism was influential in, if not fully responsible for, the hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic 1921-1923. MMT obtains “insights” from accounting relationships, but accounting relationships are merely tautologies which cannot be used to deduce non-trivial dynamics of the real world.

The first fallacy of MMT is to assume that fiat currency is the only form of money, when there are many other forms of money. Modern money is broadly defined as all media which are used to settle transactions in the modern economy. Controlling the fiat currency does not control all forms of modern money. Not all forms of money are related to the state or used for and motivated by paying taxes. Modern money as defined may include bank deposits, short-term credit created by commercial banks, crypto-currencies, gold, silver, etc. Even restricting to narrower definitions of modern money, the state does not control money.

For example, Post-Keynesians, such as Hyman Minsky (1992.5), consider as money bank deposits, which are created simultaneously with credit creation in commercial bank lending. Bank deposits are a form of money which, used with credit and debit cards, is more common than cash or currency in the modern economy. Since the state has no direct control of the creation of commercial bank deposits, MMT cannot claim to be about modern money. Therefore, MMT is a misnomer; it should be called state money theory (SMT) – the original name given it by the chartalists.

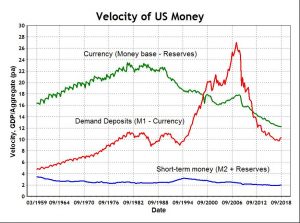

The multiplier relationships between the money base (controlled by the US Federal Reserve) and other monetary aggregates such as the constituents of M1, M2 and broader credit measures are highly unstable and unpredictable (see below). The state may influence, but does not control modern money. The chartalist fallacy is to assume the state completely controls money. This fallacy is an important assumption of MMT, because otherwise the state cannot assume to control the economy through its control of money.

The second fallacy, committed by most economists including Keynes (1936), Lerner (1943) and Piketty (2014), is to confuse money with capital. Money and other financial instruments which measure wealth are not capital, but are claims on capital which is defined as the means of production, including real resources, as well as goods and services for consumption. Money supply changes may not affect changes in capital, which has a more direct relationship with economic activities.

It is a monetarist fallacy, through erroneous interpretation of statistical correlation (Friedman, 1970), that assumes money supply can be used to control the economy. Even if central banks could control money, which they cannot, managing the economy is a delusional mandate of central banks. Classical economics is probably correct in that money is at best neutral in the long-run in its impact on the economy and at worst leads to “money disorder” and economic harm.

The monetarist fallacy is to assert that money supply has a direct or predictable impact on the economy. Money supply changes may have little predictable impact on the real economy in the short-run. In the long-run, money supply behaves just opposite to common belief of the monetarist fallacy: increasing money supply and debt has reduced economic growth. The last decade has provided a most glaring example of the monetarist fallacy: enormous currency and debt increases have produced weak economic growth. Excessive debt growth has reduced long-term economic growth due to the policy of debt and destruction of the economy.

In the modern economy, the state cannot control the money supply or capital or the economy. The reason is: for any form of money to be able to control the economy, that form of money must have a stable velocity, which is defined as the ratio of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) to the quantity of that money. The stability of velocity, assumed by Friedman (1970), is required to predict how a change in money supply will affect a change in economic output. The empirical data show that the relationships to GDP are unstable not only with the currency, but also with different forms of narrow money as seen from US data in the chart below. Different forms of money also have no stable relationships with each other. In the above chart, since the GFC, increased currency supply (green) and demand deposits (red) created from commercial bank lending did not lead to a commensurate increase in economic growth, as seen in the falling velocities of these monetary aggregates. This is a clear empirical refutation of monetarism administered by the US Federal Reserve.

In the above chart, since the GFC, increased currency supply (green) and demand deposits (red) created from commercial bank lending did not lead to a commensurate increase in economic growth, as seen in the falling velocities of these monetary aggregates. This is a clear empirical refutation of monetarism administered by the US Federal Reserve.

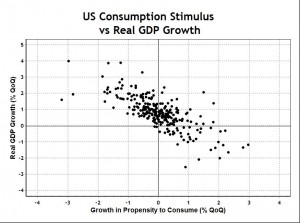

The third fallacy committed by MMT and Keynesian economists is to assume that more money can always increase consumption and more consumption will stimulate economic growth. The last assumption is the Keynesian fallacy that consumption demand drives economic growth. Since consumption includes the consumption of fixed capital which is required for investment and economic production, consumption may actually lead to less capital and less investment. Therefore, more money and more consumption may lead to less capital, less investment and less economic growth, as is evident from the history of the US economy since 1947, in the following chart.

The data show that increasing consumption faster than the overall economy or increasing the propensity to consume, generally led to lower real economic growth. The structure of the post-war US economy was such that more consumption and less investment were detrimental to economic performance. The increase in consumption did not come totally from economic production, but significantly from structural shifts caused by government spending.

The data show that increasing consumption faster than the overall economy or increasing the propensity to consume, generally led to lower real economic growth. The structure of the post-war US economy was such that more consumption and less investment were detrimental to economic performance. The increase in consumption did not come totally from economic production, but significantly from structural shifts caused by government spending.

Deficit Spending

If the government can issue spending currency at will, then government debt must be a “barbarous relic” because government borrowing would be unnecessary. So, MMT (Fullwiler et al.,2012) is puzzled why the US Federal Reserve exists all, because the government treasury can simply spend and issue currency at will or destroy currency by taxation at will (assuming there are no tax dodgers). MMT rejects that a central bank is necessary to control the money supply. It asserts, without empirical evidence, that the control of the currency by the treasury is sufficient to control inflation and achieve full employment in the economy.

The assumption that the government can simply create currency to spend means there should be no budget deficits since the government does not need to borrow. However, MMT is not telling US politicians anything new because they have already been running large deficits for decades as if deficits are irrelevant or non-existent. Debt and budget deficits are not wrong a priori; the question is what they achieve and whether they are self-extinguishing in the long-run.

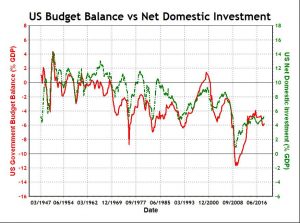

The current debate about government budget deficits between Paul Krugman and MMT (Kelton, 2019) is muddled because the arguments are not based on facts, but on the doctrines of one school against that of another. In the chart below, the fact speaks for itself.  Clearly, government deficit spending substitutes substantially private sector investment spending, not dollar for dollar, but consistent with the so-called Ricardian equivalence proposition (its conclusion if not its logic) that government deficits have little net effect on overall spending. Note also, the above chart and data suggest the private sector adjusts its investment before government deficit changes.

Clearly, government deficit spending substitutes substantially private sector investment spending, not dollar for dollar, but consistent with the so-called Ricardian equivalence proposition (its conclusion if not its logic) that government deficits have little net effect on overall spending. Note also, the above chart and data suggest the private sector adjusts its investment before government deficit changes.

The reason is: the US government issues and sells bonds through the Federal Reserve and its primary dealers in the market, then obtains money from investors (or "print currency" in quantitative easing), before it receives the money to spend for its budget. Contrary to MMT, the government does not spend fiat currency first and then “create private sector saving”. Private sector investment changes lead to changes in government spending. Or sequentially, government borrows, private sector invests, then government spends.

Our explanation for Ricardian equivalence is: any investor with money has a choice between a financial investment in government bonds (which is also regarded as “saving” to the investor) and a real investment in an operating business. The rational decision by the investor depends on relative investment returns of the choices adjusted for risk. Our explanation for Ricardian equivalence does not depend on “crowding out” in the money markets. The decision may be related to business opportunities and not simply to interest rates. Interest rates may not reflect economic fundamentals (e.g. supply and demand), because they are manipulated by central banks which, for example, could make holding government bonds riskless.

Because government expenditure is mostly for consumption, the net effect is that deficit spending largely replaces private real investment with public consumption. This substitution is harmful to an economy if it is already over-consuming, regardless of the level of unemployment. Note that government deficits lead to a loss of real investment or a loss of capital accumulation. The increase in private saving is only financial, not real economic saving. Government surplus or “austerity” may increase private real investment to balance consumption and therefore promotes US economic growth, as seen in late 1990s.

Deficit Matters

Large deficits and mountains of debt prove that operationally there has been no constraint due indeed to the state’s ability to create currency, as observed by MMT. Anxiety expressed about government finances is mostly unfounded. However, their exponential growths indicate that the economic policy has been a mistake. All that MMT is doing is to help the politicians to double down on their mistake, by providing justification to continue to accumulate deficits and grow debt, thus falling faster into the Keynesian black hole because it is a policy of debt and destruction. What is viable financially may not be viable economically.

The MMT charlatans rarely appeal to economic data and facts and rely largely on doctrinal rhetoric in their loose verbal reasoning. Their models ignore many real life issues and focus almost entirely on monetary mechanics or the control of national currency (mistaken as the only money). The MMT impact on other issues such as interest rates, inflation and foreign exchange has not been discussed adequately or convincingly.

For example, with the “exorbitant privilege” of the US dollar as the global reserve currency, the US has been accumulating persistent and growing budget deficits, trade deficits and current account deficits. While deficits don’t matter or should not exist in theory for MMT, they matter sufficiently in real geopolitics to cause currency wars, trade wars and potentially world wars, as currently witnessed. Even a sovereign currency with special global reserve status has constraints unacknowledged by MMT, as evident by many countries seeking to move away from their dependence on the US dollar.

By ignoring large and growing deficits, the enormous currency creation by the US Federal Reserve may lead ultimately to a derailment of the monetary sovereignty assumed by MMT. With a fiat currency, deficits may not matter financially until they matter economically in a collapse.

Monetary Socialism

At the heart of MMT is a faith in monetary socialism for economic management.

Monetary socialism is defined as the form of socialism where the state uses the currency it creates to redistribute capital. The state issues currency to its preferred recipients who claim existing capital and thereby reduce the purchasing power of other existing and competing claims to the same capital.

Existing claims on capital are devalued and shared with the claims of newly issued currency on the same capital. The state issued currency has no intrinsic value; it has value only when its claim is honoured and redeemed in capital. The process of currency creation does not generate capital, but merely redistributes it. The state and the financial system are effectively thieves of capital through money creation, unbacked by economic production. Monetary socialism with a fiat currency system unanchored to economic reality is a giant Ponzi scheme of limitless capital transfer which will end, like all socialist systems in history, in economic collapse when there is nothing left for the state to expropriate.

The enormous increase in money since the GFC did not cause a commensurate increase in economic growth. Indeed, the US economy has been force-fed by the wall of money from debt and quantitative easing. The growth has been artificially generated by consumption financed through debt and fiat currency creation. As soon as this flow of money slackened, due to a pause in monetary expansion, the US economy has faltered because real economic production has been progressively destroyed by constant theft.

Contrary to MMT expectations, monetary socialism has not improved economic prospects. Their explanation is that monetary socialism so far in the GFC has mainly enriched the banks which were the major recipients of the state created currency. The MMT answer is that monetary socialism should be for the masses through universal basic income, debt jubilee, helicopter money, etc. The fact which MMT ignores is that there has already been monetary socialism for the masses worth annually about 16 percent of US GDP through transfer payments in social security. The MMT economic policy will merely accelerate the monetary socialism for the masses and cause faster systemic failure due to the three major fallacies indicated above.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s formal adoption of monetary socialism for the masses will exaggerate the flawed economic policies and make the developing disaster far worse. Equality of opportunities is capitalism, whereas equality of outcomes is socialism. Opportunities stimulate vitality, while rigged outcomes sap vitality. The problem of the US economy is under investment and over consumption. The welfare and corporate socialism by the US government is not real capitalism which depends critically on entrepreneurs from a now dwindling middle class.

There is no solution for the economy other than to balance consumption with real investments in honest economic production which has been discouraged by state and financial system theft of private savings. Otherwise, the unnoticed stagflation of the past several decades will turn into something much worse.

Conclusions

Hazlitt’s famous book (1962), Economics in One Lesson, begins with the statement:

Economics is HAUNTED by more fallacies than any other study known to man.

Fallacies are at the base of MMT’s claim that with a fiat currency system, a monetary socialism can be implemented to control the economy and in particular, unemployment. Three of the most significant fallacies of MMT exposed in this paper are: the chartalist fallacy, the monetarist fallacy and the Keynesian fallacy. These fallacies are sufficient to refute MMT’s monetary socialism as a snake oil cure for the economy.

Of course, politicians and government bureaucrats are even more ignorant than academics who supply them with economic justifications for their spending on pet political projects. The economic charlatans all claim to have discovered the philosopher’s stone to create economic prosperity. To politicians, MMT sounds great: government finances have no constraints!

Keynes (1936, p. 383) was right when he observed “Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.” The academic scribbler is used to justify all manner of harebrained government schemes. The economic charlatans of MMT are the academic scribblers who are serving their socialist political masters. They want the monetary madness to continue, but for socialism.

Yes, I am still lurking. I very much appreciated this post. It is funny that you mention corporate socialism near the end. How much influence on government do corporations (or their officers) actually have? A question for another day perhaps.

In any event, one of the most important points you make is the distinction between money and capital. This could be a useful starting point to define both. Economists of all stripes seem to lack a workable or adequate definition for either, and this is a real ontological failure.

I am not sure if this is really the same thing, but I try to get my students to consider this distinction in all my classes. It is particularly salient for money and banking, though here it seems to take the form of a distinction between financial capital and physical capital. Getting some to consider this has been an uphill battle.

I had not thought about the idea that MMT assumes the government controls the money supply. Clearly the government does not control it. I knew this, but had not made the connection to MMT until I read this post. The distinction between “bank” money / credit and government money is very important and always is in times of crisis. In the financial crisis of 2007-2008 banks stopped accepting one anothers' money (note-still denominated in dollars as the unit of account in the US, even if not directly issued by the FED), and they sought instead reserves from the Fed. Marx came to the same conclusion about crisis – except that in that era, banks sought gold.

You mention the decline in investment, both in this post and in previous ones. It is disturbing to know that Keynes himself saw fluctuations in investment as one of the main causes of the business cycle, while some of his followers seem to have forgotten this. This points to other necessary distinctions which are not well acknowledged in current US political discourse. One is the distinction between public investment and public consumption. It is unfortunate that many in the US view almost all government spending as primarily consumption, when much of this could be considered investment instead.

It seems to me that the public sector has been under invested in many ways. Many of our primary school teachers in the US feel this way, and while we could correct this, we choose not to. Certain kinds of public investment represent real gains. A better medical system in the US, combined with a choice not to abandon certain segments of the population would require investment in public infrastructure to combat recent declines in the US lifespan as documented by Case and Deaton. Part of the problem is that neither patients nor doctors know the price of the services. Ironically, in places like Germany and France with ‘socialized’ medicine, a patient can know what it will cost since it is negotiated by doctors with the national health insurance system. While not perfect, it’s a key cost control measure.

While MMT is an improvement over neoclassical thinking, I do worry that it can’t deliver what it seems to be promising. It isn’t like governments haven’t resorted to this to pay for wars, or banks channeled funds to build railroads in an earlier era. Given US spending priorities, it seems to have led to Military Keynesianism on steroids. Taxes have not completely financed any war that I can think of, but maybe my awareness of history is too narrow. For the US, current ‘defense’ spending and other priorities are not paid all out of taxes, and if there is an emergency, Congress can appropriate the funds, and the Treasury will cooperate with the Federal Reserve to create and deliver them. But Vietnam, Korea WWII, WWI, US Civil War, the American Revolution, all relied on money creation in the way that MMT describes. While MMT says that the Federal government does not need to tax to spend (operationally true) deficits will matter because people think they do. This may be a side effect of poisoning people against all types of taxes, even state and local taxes. My city and state in the US are not monetarily sovereign, so they are typically more careful in their decisions. MMT does point out that real resources limit the amount of money that can be created before inflation starts. True, and it may not matter why type of money is created, whether by the government or by the private sector. Taxes paid in money may serve to remind people that government activity uses real resources – land, people, energy, etc., that have alternative uses.

I am not sure about money neutrality in the long run. Fluctuations in income have demographic impacts. The financial crisis of 2008 caused many families to delay having children, so the result is a very small cohort of 10 year olds who will be college age in a few years. Some colleges are feeling a financial pinch even now for other reasons, and this demographic trend will only add to the pressure. That tells me that money/income impacts personal investment decisions – the creation of families, the growth of ‘human’ capital, with consequent impact on long run productive capacity. You pointed out that the change in the distribution of income was hollowing out the middle class resulting in a dearth of entrepreneurial talent. The result – a less skilled labor force with long term effect on productivity and growth. If money was truly neutral in the long run, there would be no long-term impacts in either direction.

We may need to very careful, as I can see even in my own response here a possible conflation of money as such, with income and other things measured with it, especially in the previous paragraph. We should disentangle money as such from its distribution through various channels. And we may need to reconsider inflation. As traditionally defined, inflation has meant increases in the prices of consumer goods, and that may not be where it shows these days.

Again, thank you for your efforts, and giving me things to think about.

Jeff

Your comments, as an active teacher, is much appreciated. I hope you can encourage thinking rather than learning of the dogmas which are economic theories. As you suggest, I would have liked to start with definitions, but it was difficult to do in this context, may be in a future post devoted entirely to money. However, in the post, I did eventually define both money and capital:

Your statement: "It is unfortunate that many in the US view almost all government spending as primarily consumption, when much of this could be considered investment instead" is not correct according to BEA data, which show, for example, 98 percent of government spending in 2015 is consumption, explained in detail here:

http://www.asepp.com/fiscal-stimulus-of-consumption/

Of course, the difference between consumption and investment is not always "black and white" (e.g. education), but quite often it is. In any case, decades of privatization of public assets have reduced US government investments. The decay of US public infrastructure is self-evident even in the home of Hollywood e.g. LAX (LA international airport).

You said: "Taxes have not completely financed any war that I can think of, but maybe my awareness of history is too narrow". Due to FASB 56, $21 trillion of US Department of Defense spending (from the sale of US Treasuries) has not been accounted for in US government finances. Presumably, this is helicopter money for the military.

You said: "I am not sure about money neutrality in the long run". Your suspicion is correct. Classical economics assumes money creation is constraint by gold and money cannot do harm for long. Since we have a fiat currency system for nearly 50 years, money is not neutral in the long-run, but has done enormous harm, particularly since the GFC:

http://www.asepp.com/policy-of-debt-and-destruction/

By the way, credit or debt is not money, confused by some economists, because a mortgage or a government bond cannot be used to settle most transactions. Rather, the credit creation process by commercial banks creates simultaneously bank deposits which are money through credit and debit cards.

James Rickards has a leisurely explanation of MMT's chartalist fallacy here:

https://dailyreckoning.com/the-real-problem-with-modern-monetary-theory/

James Rickards (JR) says money is based on trust, but MMT says money is based on coercion, fiat or authority. The truth is: money is based on either trust or coercion or both, depending on circumstances (as discussed in the above post).

The reason why the government cannot control inflation is: it does not control all forms of money. The money which the government does not control, may behave non-linearly as JR suggests.

Here is an example of an academic charlatan lobotomizing students:

https://weapedagogy.wordpress.com/2019/03/28/failure-of-ricardian-equivalence/

The impulse of performing magic to get something out of nothing runs deep in the human psyche. Academics largely talk among themselves, untouched by reality. Mostly, economic ideas are based on loose verbal reasoning which is full of unarticulated assumptions and logical errors which students have to accept to pass their exams.

Economic "truths" are taught through made-up stories without any attempt to check their conclusions against the facts of reality. In the middle of the video at the end of his article, Zaman admitted he got his stories mixed up!

Pointing out fallacies, real or imaginary, of classical and neoclassical economics, does not validate Keynesian economics. The classical explanation for Ricardian equivalence is false, because there is no evidence that people anticipate future government policy. In economics, the opposite of a wrong is usually another wrong, because economics is neither science nor logic.

Ricardian equivalence may or may not be true universally, but empirically, it has been substantially true in the US, as this post and this blog have proved:

http://www.asepp.com/fiscal-stimulus-of-consumption/

Contrary to classical explanation, US government deficits have indeed stimulated consumption, but the data show economic growth has been reduced. The increase in total consumption has caused a decrease in private real investment, but it has been compensated by an increase in private financial investment in government bonds. Proponents of MMT are economic charlatans telling stories.